The Roots of the Atlantic Maritime Officers Association

Existing Labor Union Activity Laid the Groundwork for Forming the AMOA

There was a lot of labor union activity in the 1930s and the maritime industry played a big role. Nationally, maritime workers had suffered declining wages and increasingly untenable working conditions since an unsuccessful strike in 1921. Additionally, a major contributing factor to these trends was the Great Depression. That stated, many seamen attributed the losses to the leadership of the International Seamen’s Union (ISU), which was perceived as corrupt and inefficient. The ISU was a federation of independent unions and had its start in 1892. At its peak, it represented as many as 115,000 members in the shipping boom caused by World War 1. However, the ISU’s influence had been in decline and weakened considerably in 1934 when it lost one of its affiliate organizations, the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific (SUP).

The 1934 West Coast Longshoremen’s Strike was a defining moment in maritime labor organization. This strike was held by the International Longshoremen Union (ILU) with a main objective to take control of job distribution away from dock foremen who were often perceived as not dispensing jobs in a fair and equitable manner. The movement was centered in San Francisco, but it was a coordinated activity with other ports. It effectively shut down maritime commerce on the West Coast. Thousands of people were involved including ISU members that deserted more than fifty ships, idling them in San Francisco.

In April 1935, a conference of maritime unions was held in Seattle. An umbrella union, called the Maritime Federation, was formed to represent ISU members, maritime officers, and longshoremen.

1936 Gulf Coast Maritime Workers’ Strike was initiated by the Maritime Federation of the Gulf Coast with its main effects being felt in the Houston and Galveston areas. The strike lasted from October 31, 1936 to January 21, 1937. The Atlantic Refining Company vessels visited Houston and Galveston regularly, so this strike directly affected people on board the Atlantic ships. This strike combined with a concurrent west coast strike were catalysts for the formation of the National Maritime Union (NMU) started by Joseph Curran. Shortly after the formation the NMU, thousands of unlicensed mariners left the ISU effectively dissolving it as an organization. In the wake of the NMU formation, a second splinter labor organization, named the Seafarer’s International Union (SIU) represented the remaining seamen.

Other union activities in the 1928 to 1937 timeframe included disruptive activity by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), better known as the “Wobblies.” The goals of this organization were unclear, but the Wobblies often pursued a policy of conspiracy on ships and in the seamen’s organizations. The IWW efforts were vigorously opposed by traditional unions because their presence damaged efforts of these unions to be recognized by shipping companies. Another group opposed by the traditional labor organizations was the Marine Workers Industrial Union which was affiliated with the Communist Trade Union Unity League. Marine Worker Industrial Union was considered a radical group that was trying to infiltrate the existing unions and spread their ideology.

Another major development in this timeframe was the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) which initially comprised of eight international unions under the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The CIO wanted a much broader outreach to industry employees and its differences with the AFL caused a split in 1938. The Communist Party was supportive of the CIO initiatives and consequently, there was a cloud over the CIO based on its perceived relationship with the Communist Party. The National Maritime Union (NMU) was an affiliated union with the CIO and thus, many mariners perceived the NMU has having communist elements. The Marine Engineers Beneficial Association (MEBA) was also affiliated with the NMU and CIO.

The National Maritime Union’s influence and membership of unlicensed personnel grew quickly through active recruitment throughout the U.S. Merchant Marine. There were seamen on the Atlantic Refining Company vessels that joined the NMU. In addition to the active recruitment of unlicensed personnel, NMU members were also influencing deck and engineering officers to join the affiliated officer unions. This active recruitment process is probably the biggest single factor in triggering the formation of the Atlantic Maritime Officers Association and several other independent tanker officer unions.

The turbulence in the industry was not felt by all. Most of the major oil companies offered wages and working conditions for both their licensed and unlicensed personnel that exceeded shipping industry standards. Additionally, these companies typically offered stable employment. Consequently, many mariners on these tankers were concerned that their ships would be unionized, thus putting their livelihoods at risk. The first people to act were ship’s officers of the Socony Vacuum Oil Corporation. The Socony Vacuum Tanker Officers Association (SVTOA) was started by these officers with the assistance of a labor consultant, John Collins. The official incorporation date of the SVTOA was September 2, 1937.

John Collins, a teacher and labor consultant, played a vital role in the formation of the SVTOA and subsequently several other independent tanker unions. Mr. Collins authored a book titled “Never Off Pay” published by Fordham University Press in 1962.

John Collins, a teacher and labor consultant, played a vital role in the formation of the SVTOA and subsequently several other independent tanker unions. Mr. Collins authored a book titled “Never Off Pay” published by Fordham University Press in 1962.

Although this book is out of print it is still available and lays out the history in the early part of the twentieth century regarding the independent tanker unions. According to Mr. Collin’s book, the initial success of the SVTOA triggered a rapid succession of independent tanker officer associations being established. The victories in Labor board elections of the oil company officer associations effectively stopped the drive for recognition by CIO officer unions in the U.S. tanker industry.

By 1939, in addition to the AMOA, seven other independent officer unions had been created.

In 1939, the National Maritime Union called a strike for unlicensed seamen in the tanker fleet. The purpose of the strike was to establish a hiring hall and take control of managing the job assignments. This strike created controversy because it had not been approved by a referendum of its members per its bylaws. The strike did not have large effects on the industry, but it did alienate many of the unlicensed seaman that it negatively impacted. It was this action combined with the activity of the officer associations that set the stage for many of the independent unlicensed employee unions to be established.

In summary, the Atlantic Maritime Officers Association was started to maintain the stability in a disruptive labor market.

In summary, the Atlantic Maritime Officers Association was started to maintain the stability in a disruptive labor market.

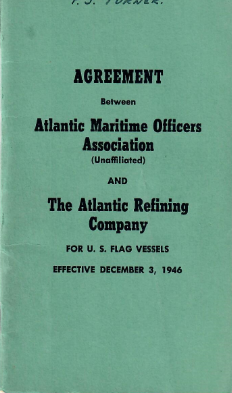

The AMOA and company completed the first collective bargaining agreement in 1938 that established wage and living conditions better than any national union contract.

For the last 82 years, the AMOA has tried to build on that original premise.