A History of the Marine Companies

As a starting point, why is the name of our Association the Atlantic Maritime Officers Association?

Answer: Our name comes directly from the Atlantic Refining Company.

The history of the Atlantic Maritime Officers Association is integral with the evolution of the companies it has served. The following narrative covers the history of these marine companies. As this section was being written, it was realized that there is a much deeper history here of the people and culture that deserves to be captured and communicated. A separate section covers the formation and evolution of the Association itself.

The original company that we were affiliated with was the Atlantic Refining Company that was incorporated in 1870. In 1874, Atlantic Refining became part of Standard Oil and acted as its refining division until the Supreme Court ordered the conglomerate’s dissolution in 1911. At that point, Atlantic Refining Company became its own independent oil company once again. John Wesley Van Dyke had been the refining manager under Standard Oil and became the first president of the newly independent company. The company soon realized it required its own fleet of ships to transport product. Atlantic Refining Company consequently agreed to a five-ship contract with Union Ironworks, a San Francisco shipyard and division of Bethlehem Steel. The first ship was the 10,200-ton S.S. H.C. Folger. She slid down the ways on October 24, 1916. The H.C. Folger was named for the president of Atlantic before its separation from Standard Oil.

The original company that we were affiliated with was the Atlantic Refining Company that was incorporated in 1870. In 1874, Atlantic Refining became part of Standard Oil and acted as its refining division until the Supreme Court ordered the conglomerate’s dissolution in 1911. At that point, Atlantic Refining Company became its own independent oil company once again. John Wesley Van Dyke had been the refining manager under Standard Oil and became the first president of the newly independent company. The company soon realized it required its own fleet of ships to transport product. Atlantic Refining Company consequently agreed to a five-ship contract with Union Ironworks, a San Francisco shipyard and division of Bethlehem Steel. The first ship was the 10,200-ton S.S. H.C. Folger. She slid down the ways on October 24, 1916. The H.C. Folger was named for the president of Atlantic before its separation from Standard Oil.

The First Fleet

By the end of the first new-build program in 1918, Atlantic had seven ships totaling at 76,200 deadweight tons with a capacity of 596,000 barrels. It was a fleet of product tankers where the main run was from the U.S. Gulf to the Philadelphia. All the vessels gave many years of service and were eventually sold or traded to the War Shipping Administration during World War II. From 1918, over the next twenty years, Atlantic gradually increased the size of its fleet to seventeen ships ranging in size from the 900-ton MS. White Flash to the 17,000-ton SS. W.D. Anderson.

Early Innovators in the Tanker and Shipping Industry

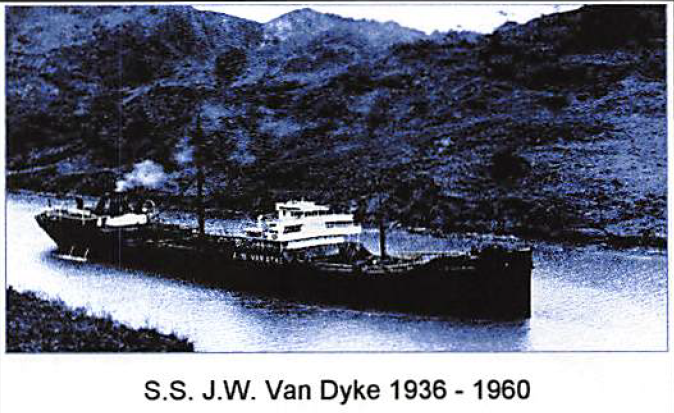

Now in the 1930s, the original Atlantic Refining fleet was aging and required replacement. J.W. Van Dyke viewed the tanker fleet as an integral part of the company and was willing to try some daring innovations. Working with Lester Goldsmith, a consulting engineer who later became the Manager of Engineering and Construction, they advanced the concept of constructing an all-welded hull. At the time, tankers were still being constructed using rivets. In 1938, the SS. J.W. Van Dyke and the SS. Robert H. Colley were the first two of seven ships to be constructed at Sun Shipbuilding in Chester, Pennsylvania that were of all welded construction. Another first for these ships were that they were turbo-electric and fitted with centrifugal cargo pumps versus steam-driven reciprocating pumps. The new pumping arrangements dramatically decreased turn around time at discharge terminals. These two innovations were important steps forward for tankers. The all welded construction made the T-2 tankers and other naval vessels of World War II possible to build in compressed timeframes.

Now in the 1930s, the original Atlantic Refining fleet was aging and required replacement. J.W. Van Dyke viewed the tanker fleet as an integral part of the company and was willing to try some daring innovations. Working with Lester Goldsmith, a consulting engineer who later became the Manager of Engineering and Construction, they advanced the concept of constructing an all-welded hull. At the time, tankers were still being constructed using rivets. In 1938, the SS. J.W. Van Dyke and the SS. Robert H. Colley were the first two of seven ships to be constructed at Sun Shipbuilding in Chester, Pennsylvania that were of all welded construction. Another first for these ships were that they were turbo-electric and fitted with centrifugal cargo pumps versus steam-driven reciprocating pumps. The new pumping arrangements dramatically decreased turn around time at discharge terminals. These two innovations were important steps forward for tankers. The all welded construction made the T-2 tankers and other naval vessels of World War II possible to build in compressed timeframes.

Years after the development of the all welded hull, Sinclair Oil was an oil company that had its own marine division that became part of Arco Marine in the late sixties. One innovative contribution that Sinclair was known for was that it developed the first tanker to only have a stern house structure. Historically, tankers had always been built with a midship house until that time.

War Service

The ships and crews of the Atlantic Refining Company were deeply involved in World War II. The War Shipping Administration (WSA) was set up as an emergency agency February 7, 1942. The purpose of the WSA was to purchase and operate civilian shipping tonnage the U.S. needed for fighting the war. The entire fleet, all twenty-six vessels, eventually twenty-nine, were requisitioned for use by the U.S. Government. Out of the twenty-nine ships, six were lost to enemy action, with a loss of ninety-seven men.

During World War II, Atlantic vessels and their AMOA officers carried crude oil and finished products on most of the shipping lanes of the world, including uncharted paths to strictly-Navy-made ports.

One well documented story was of the tanker S.S. E.H. Blum. The 19,000-ton vessel struck a mine off the Virginia Capes while in route to Texas for a load of crude oil. The entire crew was able to abandon the ship successfully. The ship was blown in two pieces with the aft-end of the vessel resting on sandbar in 30-feet of water. The bow section was almost separated from the stern but was virtually undamaged. Fifty-five Atlantic men from the marine division, personnel from the Philadelphia refinery’s mechanical department, and a Navy salvage team jumped into action. Within a few weeks, the after section of the hull was floated. The S.S. EH Blum’s sections were towed to Sun Shipbuilding for repair and on December 1st, she was recommissioned.

Rebuilding and Modernizing the Fleet

At the end of World War II, there was a prolific number of T-2 tankers that the U.S. Government had constructed for the war effort and Atlantic’s fleet needed to be once again, rebuilt and modernized. In late 1945, four T-2 tankers were acquired. All were 16,500 DWT and had been built in the Sun Shipyard in Chester, Pennsylvania. Eight more T-2 tankers were added in 1946-48 while a few older ships were traded or sold. The final T-2 procured in 1948 was the S.S. Atlantic Importer bringing the fleet total to twenty-two vessels.

At the end of World War II, there was a prolific number of T-2 tankers that the U.S. Government had constructed for the war effort and Atlantic’s fleet needed to be once again, rebuilt and modernized. In late 1945, four T-2 tankers were acquired. All were 16,500 DWT and had been built in the Sun Shipyard in Chester, Pennsylvania. Eight more T-2 tankers were added in 1946-48 while a few older ships were traded or sold. The final T-2 procured in 1948 was the S.S. Atlantic Importer bringing the fleet total to twenty-two vessels.

Post-war economics resulted in increasing costs that required the company to look for more efficient ways to transport the oil. The answer was scaling up the size of the ships. The S.S. Atlantic Seaman, at 30,000 deadweight tons, 253,000 barrels was the first of three larger ships to be built. This trend continued with even larger vessels across the ensuing years as T-2 tankers were gradually replaced. These vessels included the first Endeavour and Enterprise, 30,000 deadweight ton ships built at Sun Shipyard.

Mergers and Acquisitions

In 1966, Atlantic Refining Company merged with the Richfield Oil Corporation. Richfield Oil Corporation was the product of several other merges involving Los Angeles Oil and Refining Company and the Kellogg Oil Company.

An additional merger a couple of years later was with Kansas-based Sinclair Oil Company. ARCO wanted Sinclair’s chemical and refining operations as well as its networks of crude oil and product pipelines. From the marine perspective, Sinclair had a marine fleet and the merger combined resources.

Atlantic Richfield bought the Anaconda Company in 1977. Anaconda was involved in mining and processing of copper, aluminum, and uranium. Additionally, it manufactured copper and aluminum products. ARCO also acquired significant coal-mining operations. At the time of these acquisitions, the commodity interests held by Anaconda were under-valued and ARCO thought that its oil field technologies could be employed in the mining industry. This acquisition and the strategy employed fell short of expectations. During the 1980s and ’90s the company reversed its diversification efforts in order to refocus on its historical strength in petroleum. Some of the mining operation sites that had been shut down created environmental cleanup sites that were a big liability for the company. By the end of the 20th century, Atlantic Richfield had sold off all or most of its minerals, coal, petrochemical, and solar energy assets.

The North Slope and the Trans Alaska Pipeline System

Richfield Oil Corporation, in partnership with Exxon, made the first major discovery of oil in Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay in 1968.

Following the discovery of oil in Prudhoe Bay in 1968, a massive effort started to construct the Trans Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS). The Aleyeska Pipeline Service Company was established in 1970 to design, construct, operate, and maintain the pipeline system. ARCO held a 21.3% interest in TAPS. Concurrently, ARCO Marine was actively preparing for the new supply of oil on the west coast by building more ships designed to specifically carry crude oil. Historically, the Atlantic Refining/ARCO fleet and its crews were an East Coast operation and carried clean products, not crude oil. A huge transition for the fleet was underway. Some milestones in the process were:

- The Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act was passed by the U.S. Senate in 1973. The passage of the bill was made possible by the 1973 oil crisis but getting it through Congress still required Vice President Spiro Agnew to cast the tie breaking vote.

- Arco Marine had a large new ship construction program in progress in anticipation of the additional oil transportation requirements. Five Bethlehem Steel ships were added to the fleet between 1971 and 1975. The Arco Prudhoe Bay and Sag River, both 70,000 deadweight-ton vessels were delivered in 1971 and 72 respectively. Three larger 120,000 deadweight-ton vessels were then constructed between 1973 and 1975: the Arco Anchorage, Juneau, and Fairbanks.

- A right-of-way agreement was signed with the state of Alaska on May 3, 1974.

- The first section of pipeline for the Trans Alaska Pipeline was laid on March 27, 1975.

- In preparation for the oil to be delivered, ARCO built the Cherry Point refinery in Ferndale, WA and retrofitted its Los Angeles refinery in anticipation of the new supply.

- Oil began moving down the 800-mile pipeline on June 20, 1977.

- The ARCO Juneau was the first tanker to lift a load of crude oil from the Valdez Marine Terminal on August 1, 1977.

There were delays in the pipeline construction process that required some innovative moves by the company. During this delay, the 70,000-ton vessels, Arco Prudhoe Bay and Arco Sag River were put in service delivering oil from the Drift River Oil Terminal in Alaska’s Cook Inlet down to the west coast refineries. Additionally, the three 120,000-ton vessels were put on slow steaming operations carrying oil from Iran’s Kharg Island Terminal all the way to the Cherry Point refinery in Washington State. While the company was waiting for the ANS supply to come online, the fleet was long on tonnage. As a result, a couple of the older product ships were put into grain service to Russia.

The Booming Years of the TAPS Trade

From the first load out of Alaska, Arco Marine had started a transition. Operating ships in the Gulf of Alaska was a new operating environment. Oil delivery down the pipeline started off slow at first, but it started ramping as more production came on-line in Prudhoe Bay. The increased production required more, newer ships which only hastened the transition. By 1980, throughout down the pipeline was approximately 1.5 million barrels per day. It would continue to increase in rate until it peaked in 1988 at approximately 2.1 million barrels per day.

From the first load out of Alaska, Arco Marine had started a transition. Operating ships in the Gulf of Alaska was a new operating environment. Oil delivery down the pipeline started off slow at first, but it started ramping as more production came on-line in Prudhoe Bay. The increased production required more, newer ships which only hastened the transition. By 1980, throughout down the pipeline was approximately 1.5 million barrels per day. It would continue to increase in rate until it peaked in 1988 at approximately 2.1 million barrels per day.

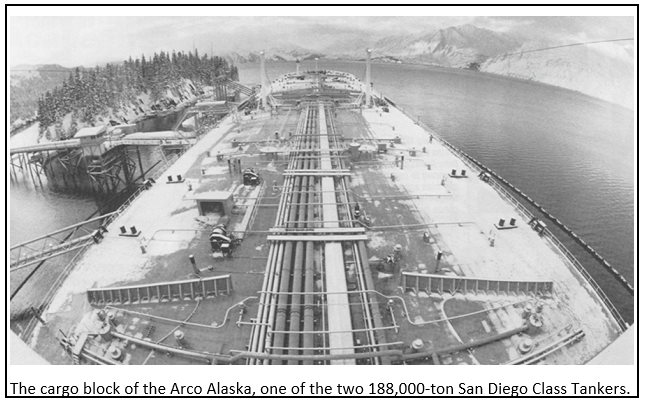

The Arco Alaska and Arco California, 188,000-ton vessels built by NASSCO, were the next two tankers to enter the fleet. They were designed to run fully loaded from Alaska to Long Beach. The vessels were delivered in December of 1979 and July of 1980 respectively. The increase in west coast oil production also increased the trade patterns. Once the 188s were in operation, they started transporting oil down to Panama. The Trans-Panama Pipeline (PTP) was under construction but did not open until 1983. Until that time, the older Arco vessels shuttled oil through the Panama Canal to Puerto Rico and the Houston area.

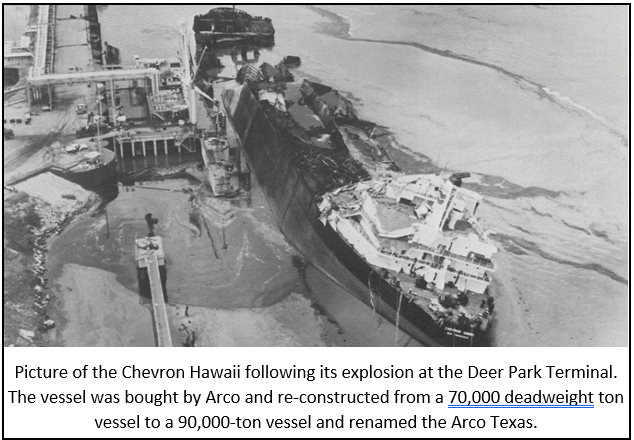

As the oil production continued to increase out of Alaska, the Arco fleet continued to grow and transform. Another ship to enter the fleet was the Arco Texas. The 70,000-ton Chevron Hawaii had suffered a catastrophic explosion due to a lightning strike while she was berthed at the Deer Park Terminal in the Houston Ship Channel. The vessel underwriters declared the Chevron Hawaii a total loss. Arco Marine ended up buying the remains of the Hawaii and had her towed to Newport News, Virginia where she was rebuilt into a 90,000-ton vessel. The original redesign of the Texas was for the ship to maximize the amount of cargo it could take through the Panama Canal. To this day, the Arco Texas holds the record for the maximum cargo transit through the original Panama Canal. Concurrently, some of the older vessels (the original Arco Enterprise and Arco Prestige) were sold.

As the oil production continued to increase out of Alaska, the Arco fleet continued to grow and transform. Another ship to enter the fleet was the Arco Texas. The 70,000-ton Chevron Hawaii had suffered a catastrophic explosion due to a lightning strike while she was berthed at the Deer Park Terminal in the Houston Ship Channel. The vessel underwriters declared the Chevron Hawaii a total loss. Arco Marine ended up buying the remains of the Hawaii and had her towed to Newport News, Virginia where she was rebuilt into a 90,000-ton vessel. The original redesign of the Texas was for the ship to maximize the amount of cargo it could take through the Panama Canal. To this day, the Arco Texas holds the record for the maximum cargo transit through the original Panama Canal. Concurrently, some of the older vessels (the original Arco Enterprise and Arco Prestige) were sold.

Another transformation for the fleet was the procurement of the Arco Independence and Spirit. These were 265,000-ton VLCC tankers that had been operated by Gulf Oil delivering cargo from the Persian Gulf. Between the two vessels, this added approximately four million barrels of cargo capacity and catapulted Arco Marine into the largest domestic tank ship company by tonnage. Part of the challenge in procuring these vessels was that they had been built using the Construction Differential Subsidy (CDS) program. A stipulation of the CDS program was that the vessels could not be used in domestic trade. Arco had made a deal to pay back the differential subsidy, but this met legal challenges by a group of independent tank ship operators. The case was fought in the federal courts for several years until Arco finally prevailed.

Another big change to the company is this timeframe was a changing of the guard. Atlantic Richfield offered a very attractive retirement option in 1985. The corporation offered a “Five and Five” package which was a credit of five years of service and five years added to your age for retirement calculations. This initiative created a sea change of leadership at all levels of the company.

This timeframe was not without its setbacks. One of these setbacks was an oil spill from the Arco Anchorage. On December 21, 1985, the ship ran aground in the Port Angeles harbor in the process of anchoring. Approximately 5,700 barrels of crude oil were spilled into the harbor. There were a couple of silver linings in this serious incident. One of those was the company’s response effort. Arco Marine was broadly recognized for taking full responsibility and active leadership in the management of containing and cleaning up the spill. Also, this incident helped shift the focus and accelerate the marine company’s transition to a more open, environmentally centered organization where safety was the top priority.

The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill and Its Effects

The Exxon Valdez oil spill was one of the single most defining events in the history of the Alaskan North Slope crude oil trade and the worldwide transportation of crude oil. Arco Marine had become leaders in the industry in terms of safety and quality by the time this incident happened so the ARCO Marine operation did not change dramatically in the immediate aftermath of this catastrophe. What did happen was the incident brought the inherent risks of the marine oil transportation business in clear focus for the larger corporation. This realization made the corporation realize the benefits of controlling their own fleet and thereby managing the risk. A direct result of this realization was an empowerment of the marine company’s leadership by the corporation to take all the necessary actions to prevent a similar catastrophic event from ever happening at Arco. This recognition in the industry along with lobbying efforts in Washington, D.C., allowed Arco Marine to play an influential role in the development of the OPA 90 legislation.

One large process that got initiated in the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez spill was another modernization of the fleet. Existing tonnage was placed on a phase out schedule. The replacement vessels were to have double hulls as set out in the Oil Pollution Act of 1990. The five single-hulled Bethlehem Steel ships that had been built in preparation for the TAPS trade were all sold or retired from the ANS oil trade.

As far as the replacement tonnage, Arco Marine at the time went well beyond the double hull requirement and moved forward with designing the E-Class tankers. These new vessels were to be not only double hull, there were a redundant ship design, classed by the American Bureau of Shipping as RS2+. The goal of developing the redundant ship was to forego the requirements of a Puget Sound tug escort. Many of the lessons learned from two decades of ANS operations were folded into the new design. The guidance from the company’s leadership at the time was to find state of the art technology in the tanker industry and incorporate it into the E-Class design without innovating. Following the design and contractor selection, construction finally commenced in 1998.

The Birth of Polar Tankers

Low oil prices created a buyer’s market for companies in the late nineties. Some examples: Exxon and Mobil merged as well as Chevron, Texaco, and Occidental. British Petroleum had also recently merged with Chicago based Amoco Corporation to become the world’s third largest publicly traded oil company. The new BP-Amoco company then put its next acquisition focus on the Atlantic Richfield Company.

ARCO had petroleum operations in all parts of the United States as well as in Indonesia, the North Sea, and the South China Sea. The company also owned and operated transportation facilities for liquid petroleum, including pipelines. The $27 billion dollar acquisition of Atlantic Richfield by BP Amoco in 2000 would double the British company’s share of natural gas in Prudhoe Bay and made BP the second largest oil company in the world.

The Federal Trade Commission (F.T.C.) would not approve the sale of the Arco’s Alaska assets to BP-Amoco. The F.T.C. claimed that it would result in a seventy percent stake in the Alaskan North Slope Crude Oil Trade that could lead to substantially higher prices for west coast refiners. BP-Amoco lost the legal challenge. Not long afterwards, Phillips Petroleum was announced as the buyer of the ARCO Alaskan operation for $6 billion. This sale included Arco Marine which within short order became Polar Tankers.

The New Millennium and E-Class Tankers

The move from Arco Marine to Polar Tankers was another inflection point in the marine company’s history. The sale of ARCO to BP-Amoco resulted in a buyout provision being presented to employees. This buyout incentivized some people to retire or move on which created some immediate opportunities for those who stayed through the transition. Phillips Petroleum did not have any significant marine operations so following the shift to Polar Tankers, the daily business of running the vessels did not see a lot of change.

The new building effort continued through the change of control from Arco Marine to Polar. The first of these E-Class tankers was the Polar Endeavour which entered service in 2001. The new double engine, diesel-powered ships came into service and gradually replaced the remaining older steam vessels and the one small tanker chartered from American Transportation and Trading Company (Polar Trader).

The Evolution of Polar Tankers

In 2002, Conoco and Phillips Petroleum announced a merger to become ConocoPhillips. Conoco had an active marine organization, so this merger created some leadership changes for Polar Tankers. Another merger in this same timeframe was with TOSCO refining. The combined marine company had a foreign flag fleet transporting oil from Venezuela to U.S. Gulf Coast operations as well as an inland tug and barge fleet. Initially, the shoreside operation of Polar Tankers continued to operate out of Long Beach, California but within a couple of the years, the company headquarters was moved to the Houston area and consolidated the entire marine operation.

Meanwhile, the Polar Tanker fleet continued its modernization efforts. There were lessons being learned daily. There was a big training effort going on to get mariners up to speed on the new ships. The reality was the knowledge base to run the new vessels was being built as they were being operated. This continuous process resulted in frequent changes being implemented as challenges were identified. These changes involved engineering, operational and procedural aspects. Our focus was on making the operation work regardless of the challenges faced. This singularity of focus may have been a contributing factor in a series of environment incidents that occurred in the late 2004/early 2005 timeframe. There were three separate incidents that all happened in quick order. The amount of oil released to the environment was not significant in terms of volume for any of the incidents, but they rocked the company to its core. A common cause for all three events was the human factor.

The solutions implemented in the wake of the incidents in the 2004/2005 timeframe really reset the company in terms of its focus on the health, safety, and environmental aspects of our operation. The Safety, Quality, Environmental Management System (SQEMS) that we operate under today was set in place during this timeframe. The Polar Tanker organization has continued to grow and evolve over the last ensuring fifteen years. Today, we continue to face challenges and navigate them without compromising our system.

In 2012, ConocoPhillips split into an upstream and downstream operating company, ConocoPhillips and Phillips66 respectively. Polar Tankers stayed with ConocoPhillips. The separation into the two companies did not have impact on the company culture, but it did change the nature of our business. We no longer had our own refineries so our trade patterns with the ships have become less predictable as a result.

Today the company continues to operate in supplying ANS crude oil to the West Coast and Hawaii. The ConocoPhillips Corporation has viewed its oil reserves in Alaska as a legacy asset. Consequently, they have invested resources and implemented new technologies in the Alaskan oil fields. As a result, oil production is set to increase in Alaska and Polar Tankers is prepared to continue providing our transportation service to the company.